Dispatches from Daegu: Part 2

Youth Code – An exhibition review

With new born eyes, the fourth Daegu Photo Biennale peers beyond its industrial cloisters of labour and machinery into re-imagined landscapes of youth and vitality. Photo credit: http:visitdaegu2011.blogspot.sg/

Prelude

A seven-hour international flight, one inter-city train and an subway ride later, I arrived at Daegu at nightfall. It took almost an hour of navigating on foot until I found accommodation – a miniscule hostel located three floors above a massage parlour run by Chinese migrants. Whimsically named “Peterpan Guesthouse”, the modest three-room apartment looks out into one of the glitziest, most expensive hotels in downtown – Novotel. In a city where contrasts align so starkly side by side, “Neverland” was truly at my doorstep.

Forever Young

The cult of youth is ironically anything but young. Researchers argue that the inclination to celebrate adolescence as the most privileged period of life is a cultural construct established since the 1920s by various historical forces.[1]

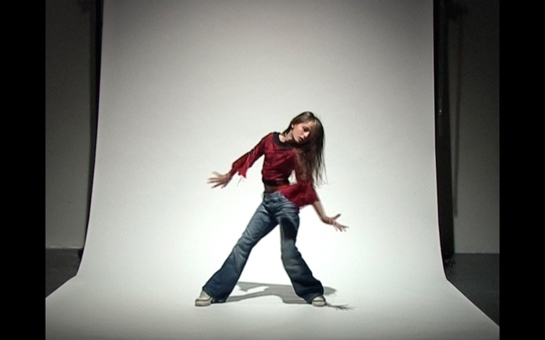

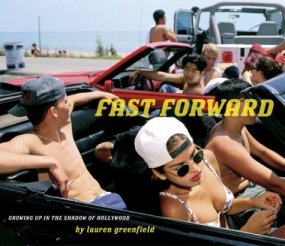

“Fast Foward” by American photographer Lauren Greenfield offers one of the most indepth and intimate views into American adolescence.

Buoyed by an emerging consumer culture, media influences and the medicalizing of old age, the social fascination with youth remains evergreen. American photojournalist Lauren Greenfield’s visceral work “Fast Forward” immediately leaps to mind when one thinks of a photo project dedicated to exploring youth culture and counterculture.

Greenfield spent four years painstakingly documenting teenagers from various ethnic and social backgrounds growing up in Los Angeles, a city of great socio-economic disparities. The images, intimate and poignant, unveiled a complex and somewhat worrying subculture of young people struggling with a myriad of issues ranging from identity to livelihood.

If Greenfield’s images were to represent the preoccupations of American youths, “The Youth Code”, a special exhibition as part of the fourth Daegu Photo Biennale, extends the discourse to a global scale.

Showcasing the works of 20 visual artists, out of whom three are native South Koreans, the month-long exhibition seeks to create a dialogue between cultures while exploring a myriad of photographic interpretations revolving round the fantasies and tensions of growing up.

Layers deep down a Global Obsession

Curated by Nathalie Herschdorfer of Switzerland, works in “The Youth Code” examine adolescence through two main approaches, though not mutually exclusive – an extraspection where photographers work closely with youths and document their observations, or an introspection, where the lens is turned inwards to nostalgically reflect and contemplate on the photographer’s experiences with growing pains. The curatorial concept aims to question adolescence as a time of rebellion or conformity, whim or gravity.

The showcase is laid out in a circumambulatory sequence that first explores a semiology of codes ranging from the tangible: body language, fashion, technology, conspicuous consumption, then transiting slowly to the intangible: belonging, solitude, authority, sexual and emotional changes.

Reading from another layer, is also about how the photographic medium itself functions as “codes” in Roland Barthes’ studies of photographs as messages — embedded meanings that express values and constitute a system of cultural knowledge.

It is also worth mentioning how the concept of the exhibiting space, the Daegu Art Factory, plays upon the theme of urban renewal and rebirth. Previously a factory manufacturing tobacco and cigarettes, the massive five-storied building was transformed into one of the city’s most vibrant arts and cultural spaces. An interesting amalgam of machine and poetry lingers on. Suchang-dong, where the Daegu Art Factory located in, is the birthplace of Lee In Seong, a representative figure of modern art in the 1930s, and continues to serve as the industrial pocket for a dense cluster of automotive, machinery, utilities workshops of modern day Daegu city.

New Life: Previously a factory manufacturing tobacco and cigarettes, Daegu Art Factory was transformed into one of the city’s most vibrant arts and cultural spaces.

Youth as consumption: Technology and Mass Media

Upon entering, one is immediately confronted first by the provocative imagery and throbbing background music of Anoush Abrar’s “50 Cent Fan Project”. Inspired by a vivid memory of Adelina in 2005, an 11-year-old daughter of a family friend, who danced a medley of choreographies seen mostly from MTV channel during a gathering, Abrar set out to track her transformation from girl to woman over six years. Every two years, Adelina would dance a choreographed routine filmed by Abrar in his studio, while being free to pick her own clothes, moves and song choices. Her songs such as “On the Floor” and “Candy Shop” are loaded with highly sexualised lyrics, and dance moves grow increasingly suggestive. The work is fascinating as it is troubling. For one, it demonstrates an unhealthy phenomenon in entertainment and mass media: exhibitionism in entertainers sustained by voyeurism in the entertained.

One gets a sense of the pervasiveness of popular culture and the music industry on youth body image as Adelina literally “grows up” on screen through an unabashed imitation of dance moves way beyond her age. Yet, watching Adelina is like staring into a mirror reflection of ourselves: our unceasing search for identity and validation amid a world bombarded with choices and saturated with desire.

Studies on the body and its interaction with space takes on a commercial spin, literally, in French photographer Denis Darzacq’s series “Hyper”. He invites young street dancers to perform big leaps in the aisles of supermarkets, and pictures them in mid-air with a quick shutter. Are they falling or flying? Darzacq, a 2007 World Press Photo Award winner for a similar series on youth break dancers, leaves things ambiguous. Floating, faceless and anonymous, these youths seemed have their individuality and personality sapped by mindless capitalist consumption. Yet, the juxtaposition seems also to challenge the mechanical orderliness in these shrines of mass production, very much similar to street dance as a counterculture. Neat racks of personal grooming products promising beauty and desirability, food consumed to sustain not just life, but ‘health and vitality’ all stand in terse tension with the bodies that consume them but now tries to reject them.

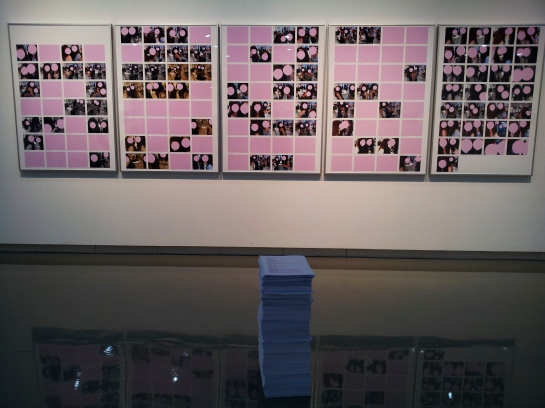

Issues of voyeurism, narcissism, technology and surveillance take center stage in Dutch artist Willem Popelier’s “Show Room Girls”. During his project collecting photos taken with webcams of showroom computers, Popelier discovered over a hundred pictures of girls who photographed themselves in various mall webcams. As one of them wore a necklace bearing her name, Popelier was able to track her down social media, accessing her tweets and personal information. His work involved arranging their webcam snapshots in a mosaic style, masking their faces photoshopped candy pink circles – like how images of criminals or obscenities are blurred on TV. Like Abrar’s work, Popelier’s works provoke thought about the gaze in art. Are their subjects (consciously or unconsciously) addressing a male or female spectator? His method of re-appropriating found images also raise questions about artistic license and what constitutes an artwork.

Into Secret, Private Territories

As the exhibition progresses into the realm of the personal and private, the space correspondingly curves into tighter compartments. The series “Tete a Tete” comprises of intimate moments Martine Fougeron has captured of her two teenage sons when they were growing up from the age of 13 to 19. Secretive worlds of adolescence often off limits to parents – smoking, sleepover parties, social experimentation, rebellion and awkwardness – surface in plain view. Yet, Fougeron’s gaze was never prying, critical, or moralizing. The frequent use of a first person persepective as a narrative device (subjects responding to the camera) suggests a great level of comfort between her and her subjects, as though Fougeron was one of them. Contrary to Sally Mann’s controversial portraits of her children in “Immediate Family”, where innocence is often overshadowed by tinges of suggestiveness, sexuality and menace of an unknown world, Fougeron’s work seek to capture flitting moments overlooked in the milieu of daily life. Often suffused with clean, even lighting reminiscent to that in traditional Dutch paintings, her frames look almost like film sets where the audience, and Fougeron herself, wander in recollection of their own childhoods.

Next, venturing further into domestic realm is Julia Fullerton-Batten’s series “Mothers and Daughters”, exploring the complexities of mother and daughter relationships through the practice of tableau-vivant photography. Autobiographical in nature, her pictures draw upon personal memories of interactions with maternal figures in her household. Her approach is part documentary and part choreography. Using actual mother and daughter pairs, she stages her subjects within their domestic settings the way a film director works on a set, creating narratives exploring their emotional bonds.

Tableau photography, whose roots can be traced to 18thor 19th century figurative painting, often draws upon a shared pool of cultural knowledge as reference points.[2] In Batten’s case, she seems to reference the rules of composition in classical paintings of Madonna and the Child. For one, lines of sight constructed by the tallest seated figure of the mother and placement of still life on the floor in The Divorce create a triangular composition very much like the one in Leonardo da Vinci’s painting of Madonna On The Rocks. The mother and daughter figure also resembles the18th century Rococo style painting “Madonna and the Child” by Italian artist Pompeo Batoni, except that the position of the touch is reversed. The gesture, meant to represent the maternal bond between mother and child, seems to take on darker undertones in Fullerton-Batten’s version. What appears to be a tender moment seems pregnant with a simmering sense of threat and foreboding. The awkward placement of fruits, traditional symbolisms of fertility, on the floor seems to suggest a compulsion to conform and suppression of identity between the women. The ambiguous facial expressions of the subjects, withering flowers, plucked fruits and sliced watermelon orchestrate an ambience fraught with psychological drama. Likewise in “Alabaster Doll”, a young lady dressed up for an important function stands on a chair while her mother grasps her wrist in what seems like an unwillingness to part. The unique nature of staging is such that despite being rooted in true experiences, pictures can never develop into full narratives. This brings forth a sense of unresolved tension and enigma.

The Daily Exhuastion (2010)

Installation comprising of newspaper-zines laid out on a wall and across a low pedestal.

Anouk Kruithof

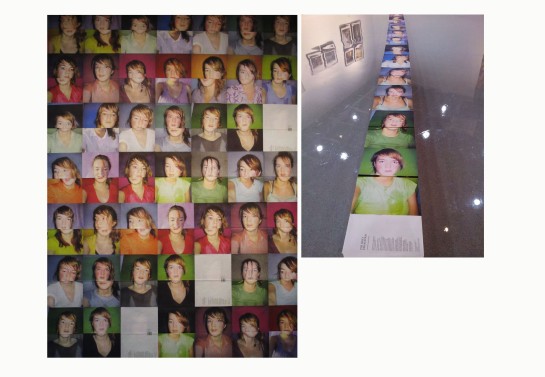

Dutch artist Anouk Kruithof hands over the power to intervene in an artwork, to the audience. A photographer by training, Kruithof constantly challenges the two dimensional limitations of pictures by exploring them as video and spatial installations. Her exhibiting work, “The Daily Exhaustion”, is an installation consisting of pages of a newspaper-zine made up of 23 self-portraits of the artist in sweat after physical assertion, displayed on a wall and onto a long, diagonally placed pedestal.

Shot against different wall colours, the portraits create a vibrant spectrum representing the varying moods and energies of Kruithof’s struggles as an artist.

The approach of using a photo book as artwork is worth closer examination. Once an object of mass production, it has been re-packaged by the art market into a prized commodity of scarcity and exclusivity. The book is perhaps the most effective vehicle through which to present and disseminate a body of photographic work, as it is easily portable, has a long lifespan extending beyond an exhibition, and hence contents retain great potential for re-discovery. [3]

Yet, Kruithof’s approach defies conventions of a typical book as having a start, middle and end. With each portrait printed across two pages, audiences are free to create infinite permutations of half-faces each time they shuffle the pages. There is no sequential order dictated, and the artwork evolves after every interaction with the audience. While most photo books are self containing and self referential, Kruithof’s work plays on how the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Unlike earlier works of Abrar, Fougeron and Popelier,

” The Daily Exhaustion” doesn’t abide by a definite linearity of time. The act of flipping through pages implies a cyclical pattern, like a weariness that repeats itself day by day.

The Personal is Public

Located in the southeastern part of South Korea, Daegu is the fourth largest city with a booming manufacturing industry.

The unique characteristics of Daegu also paints a significant context for this exhibition. As the fourth largest city in South Korea, its economic lifeblood was built upon being a southern supply chain of auto parts, mobile phone hardware, heavy metals and machinery for neighbouring industrial cities which in turn manufacture globally known brands like LG, Samsung, Hyundai. Industrial prowess also happens to be the pivot in Korean history. It was rapid industrialization and modernization which lifted the country out of years of underdevelopment during Japanese colonial rule (1910-1945) and later the Korean War (1950-1953), which cleaved the peninsular apart into North and South territorially and ideologically. Industrialization also ushered in easy access to information. In a nation with reportedly having highest internet speed in the world, Korean photographers gradually caught up with aesthetic movements abroad. With increasing affluence, more and more young artists are migrating overseas to live and study, bringing back with them hybridized experiences and influences upon return.

South Korean artist Kwon Ji-hyun, who studies in Berlin, is one of them. In her video work “Dormitory”, she examines the concept of territory and the tensions between private and public domains. Korean students are given dormitory rooms at random and they can’t pick their own roommates. Within the small space which doesn’t seem to have any privacy, their personal life is completely open to each other – be it their personal likes and dislikes or even their social circles beyond the dormitory. However, an impenetrable wall of solitude exists between each pair. Aside from the tangible lines of division such as laundry lines and pails demarcating territory, there is indifference deep inside them. The reluctance to form strong bonds is due to the fact that roommates stop seeing each other at the end of semester – their arrangement is one of convenience. Kwon implies the emotional distance between various pairs of young people occupying the same space by flipping half side of the video periodically to create random combinations of roommates, each immersed in their own activities.

The dormitory for Kwon is a microcosmic depiction of Korean society at large, which like all developed nations, face a shift from Gemeinschaft (strong reciprocal bonds of sentiment and kinship) to Gesellschaft (impersonally contracted associations between persons). Kwon, a Seoul native, born in the 1980s witnessed dramatic urban changes which were especially pronounced in the capital city. As Anne Wilkes Tucker observes, “Although younger photographers express no undercurrents of lament for past traditions as experienced by older photographers, they are acutely aware of the conflicts and complications of a dense urban existence”.[4]

Moreover, the work also provides a lens into studying gender differences as one observes interesting differences between male and female dorms – such as the choice of furnishings and personal details. The flipbook format of the video resembles that of Anouk Kruithof’s newspaper-zines and placing both works near each other create an provocative dialogue about youth issues across different mediums.

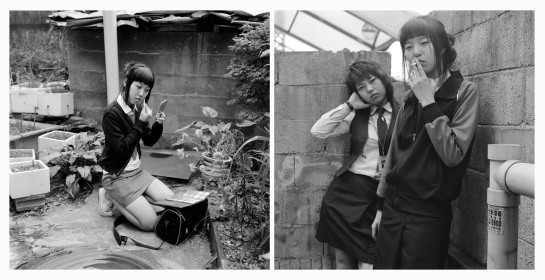

Delving further into the world of youth students is Korean photographer Park Sung Jin and his black and white portraits “Kid Nostalgia”. Shot over a duration of eight years in Seoul, his native hometown, Park reveals teenagers and teenage relationships beyond the watchful constrains of the school compound.

Revisiting back alleys, nondescript corners of the city and areas he spent his own childhood before leaving for studies in New York, he delves into a private world of young people tethering on the edge of deviance, adulthood, sociality and self-consciousness. His subjects, predominantly girls, spot cropped bangs, hitched up uniform skirts and an occasional cigarette dangling from their lips like an accessory.

Unlike Fougeron who works like a non-intrusive observer, Park goes all out to make his presence felt. Most of his subjects’ gazes confront the camera straight on, as if challenging the viewer to judge them, to blow a whistle on their waywardness. Yet, their bravado of confidence belies a sense of awkwardness and vulnerability.

A girl kneels amid a neighbourhood garden, furiously brushing on makeup as though she is afraid to be caught. Another clutches a soft toy as she sits on the steps with her cartoonish slippers. Even when pictured with their friends, they mirror each other’s poses and fashion tastes, as if caught in a dilemma of wanting to be individuals yet desiring acceptance from others. Korean society, steeped in Confucian values, practises a strict hierarchy that demands respect to be given according to age and status. In such a context, youths are often the group faced with the greatest social pressure of deferring to authority. It is only perhaps in Park’s pictures that they get to bask in the rare spotlight and express their identity. The project may also be an avenue through which Park relives memories of his teenage years upon return from the U.S., an experience which would no doubt have made him view home in a different light.

Double Edged Sword

Artworks in “Youth Code” examine how the body serves as landscapes enacting the struggle of ideologies and power relations pertaining to youth.

Ironically, the construct and polity of youth – this social network institutionalized as a power-dominated domain – thought to be dynamic and rebellious, has set the standards for conformity. Despite the diversity in interpretations that artworks have managed to flesh out, one similarity remains. An overwhelming majority of works seem to lean towards portraying female subjects regardless of the gender of the photographer. Perhaps the female form, with its traditional connotations of innocence, purity and fertility is unconsciously associated with the phenomenon of youth? Photography, like most forms of visual expressions, seems to be unable to shake off the dominance of the male gaze. According to John Berger, women in European art from the Renaissance onwards were depicted as being aware of being seen by a (male) spectator , and that the image of the woman is designed for the visual consumption of a male audience.[5]

It is also interesting how “transgressive” behaviors in female adolescent subjects are more likely to embody a less flattering connotation while for males, it is considered a rites of passage into manhood. For instance, how different would it be if Abrar’s subject was male?

The medium of photography is also worth exploring. Despite being a relatively young art form as compared to the painting tradition, photography in this exhibition has explored its potential to go beyond the two dimensional plane into 3D and even 4D. Yet its capacity to immortalize fleeting moments is both a strength and limitation. To quote Heather Addison on her studies of the motion picture camera , “to say that beauty fades like a flower is not poetry in movie language. It is hard practical sense. The camera demands the beauty of freshness and sweetness.” The camera, being an equipment of precision, casts a critical eye on what constitutes youthful appearances.

Because of photography’s visual emphasis, the exhibition could only go as far as reinforcing the cult of youth, but falls short of representing more abstract and unconventional dimensions that are not visually apparent.

Interestingly, the needle-sharp precision in curating could well be the show’s greatest injustice – for what is lacking seems to be a burst of youthful energy, a genuine spirit of spontaneity and absurdity, and a willingness to truly let go and set one’s heart free to roam.

Read about Rinko Kawauchi’s exhibition at the Daegu Photo Biennale here.

[1] Heather Addison (2006). Must the Players Keep Young?: Early Hollywood’s Cult of Youth. Cinema Journal Vol. 45 No. 4 (Summer, 2006), pg- 3-25.

[2] The Photograph as Contemporary Art. (2009). Charlotte Cotton. Pg. 52. London: Thames & Hudson.

[3] The Rise of the Photobook in the Twenty-First Century (2010). Elizabeth Shannon. St Andrews Journal of Art History and Museum Studies, Vol.14.

[4] Sinsheimer, Karen., Tucker, Wilkes Anne., Bohnchang, Koo. (2010). Chaotic Harmony: Contemporary Korean Photography. U.S.: Yale University Press.

[5] Berger, John. (1990). Ways of Seeing. Pg. 49. UK: Penguin Books.